Subha Prasad Nandi Majumdar

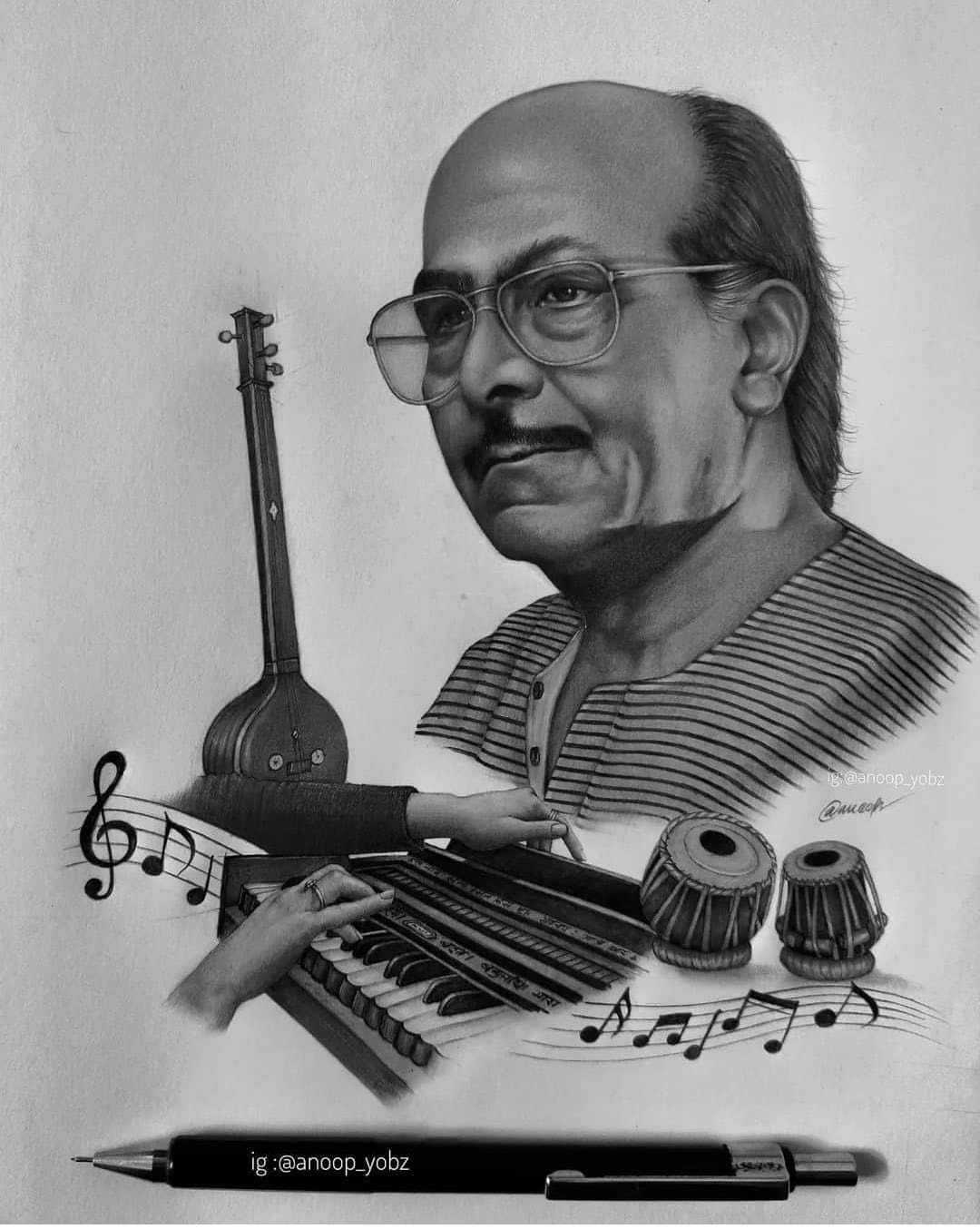

SALIL Chowdhury has completed a hundred years. The entire nation knows him as a legendary composer. Today’s celebrated music directors like A.R. Rahman and Ilaiyaraaja regard him as their guru. The debt popular music owes him is true enough—but it is not his whole identity. His contributions are spread across literature—poetry, stories, drama—and cinema. It is also important to remember that in one phase of his life, he was an active political worker and organiser. He worked among some of the most marginalised sections of society. He was at the centre of militant peasant struggles. With police warrants hanging over his head, he went underground and stayed for days on end in peasant villages. It is said that there were orders to shoot him at sight. Even as he lived such an intensely political life, he was writing songs, composing plays. The revolutionary transformation he brought to Bengali and Indian music began during this very period of political activism.

Few know that Salil Chowdhury was an excellent flautist, or that his first lessons in flute came from a tea-garden worker. His first song was written for the needs of the peasant movement in 24 Parganas. His poetry was written as manifestos of political struggle. His becoming a communist and his becoming a composer are intertwined; one cannot be understood without the other.

His contribution was not limited to Bengali music. Just as he was a craftsman of revolution in Bengali songs, he ushered in a new era in Hindi film music. Through his work in Malayalam cinema, he brought a turning point in Malayalam music as well.

To understand such an exceptional creator, one must also cast light on his remarkable life.

Salil Chowdhury was born on 19 November at his maternal uncle’s home in Gazipur village of today’s South 24 Parganas. According to passport records, he was born in 1925. But his own writings and the accounts of close relatives offer differing years—some say 1922, others 1923. Over the last one year, his birth centenary has been widely celebrated in West Bengal. Except for Rabindranath Tagore, perhaps no other figure has had such large-scale, nonpartisan centenary celebrations.

Salil’s childhood passed in tea gardens surrounded by hills and forests. His father was a doctor in a remote tea garden of Assam. A passionate lover of Western classical music, he had a vast collection of records by the great composers. Listening to the symphonies of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky was his chief form of entertainment. Salil’s mother loved Bengali songs and had her own collection of records. After finishing her household work, she would listen to records of Kamala Jharia, K. Mallik and others, or read the latest issues of leading literary journals.

Added to this was the world of the tea-garden labourers—people from various Adivasi communities brought from different regions of India. It was in this life that he first encountered the folk music of these communities. His father was inspired by nationalist ideals. Once, when a white officer made derogatory comments about Indians, Salil’s father struck him and broke his nose. Because of this incident, the family had to leave the tea garden overnight and return to their village home in 24 Parganas. Thus, Salil came in touch with the folk traditions of rural Bengal.

For studies, Salil was sent with his elder brother to his uncle’s house on Sukia Street in North Kolkata. His uncle’s son had an orchestra that played background music in silent films. Through this orchestra, Salil received training in various instruments. The geographic diversity of his upbringing—the tea garden of Assam and the Northeast, the rural environment of 24 Parganas, the urban world of North Kolkata—and the varied musical streams he heard in these places laid the foundations of his artistic personality.

He completed his schooling while staying at his maternal uncle’s house in 24 Parganas. On his way to school, he first saw the red flag of the communist party in a sweepers’ colony. He was eyewitness to the brutal police assault on striking sanitation workers—his first encounter with state repression and the resistance of working people.

After passing his matriculation exams, he joined Bangabasi College in Kolkata, where he came in touch with left-wing student politics. Inspired by this new consciousness, he and his friends started a night school in that same sweepers’ colony. At the same time, he became involved with the peasant movement in South 24 Parganas. His first song was composed from the need to spread the message of this movement. He wrote many more such songs spontaneously—most of which are now lost. Alongside political work, he also joined a dance troupe as a professional flautist.

In 1944, at the conference of the left-wing student organization in Rangpur, he wrote his first major mass song. At the time, sham trials of freedom fighters were being conducted. Public anger against the colonial judicial system was simmering. Salil gave voice to that anger in his song “Bicharpati, tomar bichar korbe jara aj jegechhe sei janata” (“Judge, it is the awakened people who will judge you”). The song created a sensation. Its lyrics, tune, and mood were all unprecedented—as if Bengal’s struggling masses had been waiting for such a song.

Across Bengal, left-wing cultural groups were emerging to organize people in the fight against fascism. New plays, new songs, new literature were being created. Experiments were ongoing about what form these new songs should take. Some were setting new words to the tunes of folk songs; others composed following the format of Rabindranath’s style. Salil’s song pointed toward a new path. With remarkable skill, he transformed a devotional melody into a fiery protest song. The lyrics were written in the everyday language of common people. The flautist Salil was reborn as a composer and lyricist.

Yet his life was not confined to music alone; he simultaneously became a communist organizer of the peasant movement. As a member of the communist party, he travelled from village to village in 24 Parganas, organizing movements. To spread the message, he wrote new plays and composed new songs. The model of mass songs he created became the standard for IPTA.

During the height of the Tebhaga movement, he wrote “Hey samalo dhan ho”, “O ay re o bhai re”. The militant spirit of the peasants found voice in his songs. At the same time, communal riots were being engineered to break the unity of the people. To strengthen working-class unity, Salil wrote “O moder deshbasi re”, set to the tune of Assam’s Bihu.

On 29 July 1946, workers’ unions called a nationwide strike. Railway workers’ leader Biresh Mishra requested Salil to join him in North Bengal and Assam for propaganda work. The railway workers attached a passenger coach next to the engine of a goods train for their campaign. At each station, Biresh Mishra spoke in support of the strike followed by Salil’s performance. Between stations, he wrote new songs, drawing themes from Biresh Mishra’s speeches and tunes from the diverse musical experiences of his childhood. The rhythm of the moving train seeped into the rhythm of his songs. He wrote countless songs on this campaign—most lost. One song, “Dheu uthchhe kara tutchhe”, survives as an unforgettable creation and is still sung by struggling people.

During a rally at Kolkata’s Shaheed Minar supporting the strike, Salil—then underground—led the singers. The police were prepared to arrest him right after the performance. He escaped with remarkable cunning, moments after the song ended.

In this political context, he wrote his extraordinary poem “Shapath” and the play “Arunodoyer Pothey”—an adaptation of Irish playwright Lady Augusta Gregory’s “The Rising of the Moon”.

During this period of activism, Salil began to question what the broader cultural movement should do. He felt that songs for marches, meetings, and slogans could not be the only work of a people’s artist. Songs of personal love, joy, sorrow, hope, despair should not be neglected. He asked: After returning home from a procession, what will a marcher sing? Will they return to traditional religious or commercial songs? Should there not be a new kind of song for their moments of leisure and love? This was not merely personal dissatisfaction—embedded in it were deep aesthetic questions about cultural politics and the people’s culture movement. These concerns appear in many of his songs from this period—songs not directly political but deeply political in their undertones.

The period when Salil was active in IPTA was tumultuous—from Quit India in 1942 to the great Bengal famine, from Tebhaga to communal conflict, from British rule to independent India. The communist movement too experienced ideological shifts and debates—from P.C. Joshi’s era to the Ranadive era, from Telangana to the first general election. Between IPTA’s founding conference in Bombay in 1943 and the seventh conference in 1953, it went through many internal conflicts. Salil’s personal life was full of hardship—an ailing father, five siblings, and a family dependent entirely on his income, which consisted only of the small allowance of a full-time party worker. Political, organizational, and personal crises all cast shadows over his artistic life.

To earn a livelihood, he entered Bengali films as a music director. Friends arranged for Hemanta Mukhopadhyay (better known as Hemant Kumar outside Bengal) to record his songs. But companies would not publish militant movement songs. Hemanta requested him to write “another kind” of song. Salil had seen from close the villages devastated by the famine and had begun writing a song based on that experience. Hemanta liked it, and at his request Salil completed it. Thus “Kono ek gayer bodhur katha tomay shonai” (“Let me tell you the story of a village bride”) was created—and its release brought an unprecedented revolution in Bengali music. The tune and lyrics were entirely new. For the first time, the life of a famine-stricken rural woman appeared in mainstream commercial music.

At that time, Salil was underground, with orders to shoot him on sight. He was not present at the recording; he was hiding in peasant villages for political work. Thus, a new era of Bengali music began at the hands of a communist party member living in hiding.

But not all his comrades were pleased. Many criticized him for joining commercial Bengali music or films, calling it a compromise. Some criticized the Western influence and use of harmony and symphonic structures in his music. In IPTA’s seventh conference, Hemanga Biswas engaged him in a historic debate. Hemanga argued that IPTA songs must rely solely on the folk music familiar to workers and peasants. Since they did not understand Western harmony, its use was meaningless. Salil, unsurprisingly, disagreed. He argued that IPTA represented a new and international ideology; therefore, its music must also be new and draw from everything—Indian folk, classical ragas, Western harmony and symphony. The result would still be Indian or Bengali, but enriched by global elements. Hemanga later admitted that Salil’s position had been correct, and that he himself had over-emphasized folk forms.

Salil also worked in Bombay cinema—first as a scriptwriter. His story “Rickshawala” became the film Do Bigha Zamin (1953, dir. Bimal Roy). The music for the film was also composed by Salil. The film shook commercial Hindi cinema; its story of a landless peasant turning a rickshaw-puller in the city marked a new era. Salil’s music astonished listeners—new tunes, new textures, new moods. Bombay’s music world sharpened and enriched his experiments with Western techniques. His IPTA experience formed the base of these innovations. He often said that IPTA’s all-India conferences were for him like Maxim Gorky’s My Universities—a living school where he learned folk traditions of various Indian provinces and protest songs from around the world.

Some critics accuse him of abandoning IPTA for Bombay. But in reality, he did not leave IPTA behind; he carried it with him. From Do Bigha Zamin to hits like Madhumati and Anand, the imprint of IPTA is unmistakable. Madhumati’s story was by another IPTA figure, Ritwik Ghatak. In the early 1950s, an alternative aesthetic strand in Hindi cinema emerged—largely shaped by IPTA people.

Salil held firm personal principles. He never composed music for films based on religious superstition or deities. Beyond Bengali and Hindi, he contributed significantly to many other Indian languages.

Although Salil’s direct involvement in organized politics ended in the early 1950s, he remained a political person all his life. His faith in communism and his ties with the communist party remained unbroken till his death. In an interview published in The Telegraph on 21 November 1993—two years before his death—he spoke of Marxism’s influence on his music and expressed political concerns that reveal his foresight. A few excerpts:

Q: What is your greatest fear?

A: That India may someday be ruled by fanatics who will silence the voice of reason, and intellectuals will be singled out and shot.

Q: Who or what has been the greatest influence in your life?

A: The great masters of both Western and Indian music and their collections of records, and an old gramophone owned by my father. Philosophically, the dialectical and historical materialism of Marx and Engels.

Q: What is your favourite dream?

A: That all men should be equal.

Q: What is your nightmare?

A: Fascism.

Barely a year after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, Salil seemed to clearly foresee Narendra Modi’s India. And even in the atmosphere of the collapse of the Soviet Union and socialist countries of Eastern Europe, his faith in Marxism remained unchanged. During a visit to the United States, he once remarked: “Once a Marxist is always a Marxist.” That would be a fitting epitaph for this musical child of the Indian communist movement.